"Human Accomplishment" by Charles Murray

Charles Murray is an American Sociologist who is most famous for "The Bell Curve" -a book about IQ. In our degenerate age, the concept of IQ is considered .... problematic, due to the popularity of leftist conspiracy theories, so he is widely and unfairly demonized. I've cultivated deliberate ignorance on the subject of IQ, just as I have cultivated deliberate ignorance of other politically charged subjects (aka Climatology), as I am not really interested enough in such subjects to make them into an all consuming argument lasting the rest of my life. There are huge industries around these subjects, industries supported at all levels of government which would be threatened if their assertions were actually proven to be incorrect. While mythbusting is fun, and noticing that "experts" are superstitious morons is salubrious for society, you have to pick your battles, and I leave it to guys like Murray or Ed Dutton to be the Galileo of this sort of thing. I stick with stuff I am more curious about.

"Human Accomplishment" hasn't much to do with IQ, except what comes downstream of it. It is the result of Murray applying a scoring model to mentions of significant human accomplishments in encyclopedic reference material. He also throws a little linear regression at various factors to assess their importance. It's a flawed model, in that there are various sample and time oriented biases cooked into his sample set, but like many flawed models, it is useful, and produces the kinds of results you'd expect to be close to correct. Now a days, you might try something similar with search engine data, or Wiki data, and you'd probably get something like the same answers in whatever scoring system you might come up with. You can browse his data here: https://osf.io/z9cnk/. Here's an example of his results on a topic I know something about:

You can see some of the biases to it; recent stuff of the 1900-1930s heroic age of physics is biased upwards, and older stuff is discounted. While most would agree that Newton and Einstein are of the highest rank, Newton was a far more impressive figure (he comes out much higher in "combined sciences" -larger sample size). Similarly, Rutherford was of towering importance, but higher than Faraday? Naaaah, probably not; Faraday was the man. Murray himself notices these peculiarities and like all good statisticians, attributes them to specific biases in his data. But all of these esteemed gentlemen belong somewhere on top of any rating of great physicists, and his model sussed it out. It's a model after all. If you didn't know anything about physics and applied his model to his data set, you would have a halfway decent guide to what you should teach physics students. The other rankings I know something about, Astronomy, Western Philosophy, Western Music, Mathematics and (to a much smaller extent) Chemistry also look pretty good. Technology looks pretty OK, though mentioning Wilkinson without Maudsley seems to indicate some odd bias in his data set. Happily the model has a relatively low reliability score, so we are provided with some indication of its unreliability from the data itself: pretty much this is the best you can expect from a statistical model.

Where the model shines is in providing "out of sample" view into the many subjects I know little to nothing about. Chinese or Indian philosophy, Chinese painting, Japanese literature, Arabic literature.... Even in Western literature there are some surprises due to my general ignorance. I've never contemplated reading Moliere; is he better than Gil Vicente? I've also never read Euripides, despite having motored through a bit of Sophocles, Aristophanes and Aeschylus. Maybe they're close behind; either way it couldn't hurt to poke at these authors who are at present unknown to me. Generally speaking I haven't the slightest idea where to start with something like Japanese art; this model provides a useful guidepost to soaking up some of the best that human beings have to offer.

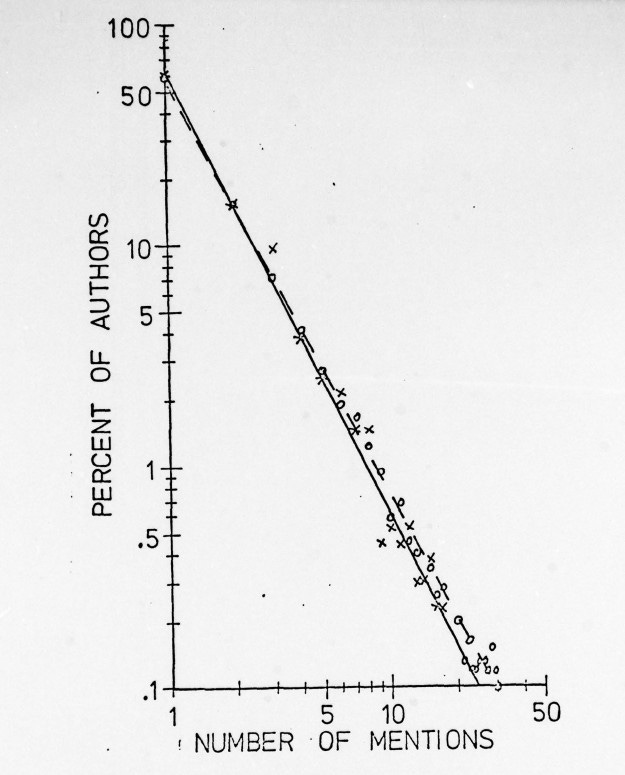

One of the valuable insights I got from this is the concept of the Lotka curve. We know that human talents, like human height and physical strength are distributed via the Bell Curve; the Gaussian or normal distribution. Somehow human achievement isn't, and this fact requires explanation. Human achievement and fame is generally power-law. I think this is one of the most important sections in the book, though his explanations are somewhat weak (he's writing for an audience which requires explanation of basic statistics in an appendix). I think he basically gets the explanation right: if you're just a little bit better at high levels of achievement, that tiny edge will make you look that much more productive. So, the more onerous the filter the bigger the curve. He also throws a sort of utility theory at the problem, which is another way of looking at the same thing (one ignored in the literature FWIIW: I'm pretty sure you can derive Lotka from a utility model -though nobody has to my knowledge done so).

Lotka in log space

Another valuable thing about Murray's book is his agreement with me that scientific and technological production are decreasing over time. Byrne Hobart originally pointed the book out to me when I first publicly made this assertion, probably around 2007. This is something people are beginning to accept now, but even 10 or 15 years ago when I started saying it, was labeled as crazy talk (Murray was well ahead of me in 2003). He also points out that other aspects of cultural production: the arts, literature, etc, are also looking similarly green about the gills. This may be less fair, as things like plays and serious novels have largely been turned into a Veblen good -perhaps the cultural energy of literature and painting has gone into film making and video games. Though in the last 5-10 years film and vidya hasn't exactly covered itself in glory either. Similarly, I've always said the computard physically interferes with technological progress in many ways. Perhaps they also interfere due to the fact that a smart dude can make a half million a year debugging Facebook infrastructure -maybe this is partially why contemporary physics is such ridiculous garbage. I doubt it though: electrical engineering was similarly profitable in the heroic age of physics.

He also provides what he thinks are some reasons for strong cultural production and its decline. The Aristotelian idea encapsulated in Maslow's hierarchy of needs is his first one, and I agree that it seems like a useful ideology to have (aka striving for excellence and the use of all your powers). Humanity always leaps forward when Ancient Greek ideals are supreme, and this is probably part of the reason for it. Striving for excellence is enormously satisfying; Aristotle tells you why in his Ethics books, or you can go read Alasdair MacIntyre's "After Virtue" for more if you can't read old books. I don't buy his one-liner that he cribbed from Bruce Thornton; rationality has nothing to do with it -Nietzsche and the will to power is more accurate. Now you don't need this as an ideology to do great things, but it helps, because, frankly, being good at things doesn't occur to most people. I remember a Russian guy I knew was confused by why I'd lift weights or read math books or whatever: his peasant ethics was entirely based on pleasure rather than excellence.

Murray also attributes much ideological power to Christianity, as it found through Thomas Aquinas a way of reconciling Aristotle with religion, and religious views themselves as having useful ideological content. He then careens off into ideological detail about Lutherans and what not which may or may not be true: certainly for recent achievement the protestant nations did better. His argument falls over though: he compares later Christianity and Golden Age Islam -Golden Age Islam looked pretty good at the time, and one might have written a book back then about how Islam was supreme for doing science. The efflorescence of science, including the contributions of Aquinas and the invention of the scientific method in the 13th century also escape his attention: while it is a popular view in current year, it is an absurd mistake to disparage this era of Christianity. Something wild was happening then that drove humanity forward forever. Murray doesn't notice it.

Elite Cities of course were a factor; Iron sharpens Iron, and while it's often the case that a genius may come from the countryside, he generally does his best work in a city with other people of genius. There is a sort of critical density of talent at which point genius can flourish. Though he doesn't say so, I think it's also true of people working together in a firm or laboratory: I've mentioned Maudsley's lock shop as being one of these centers of excellence, producing dozens of billionaire industrial magnates. These days we all know about the Paypal Mafia, and people who worked at Netscape all did pretty well. Other examples abound: Bell Labs had certain laboratories which produced many geniuses (others which did nothing of note), and the people involved in early Rentech were all great innovators; some continue to do so. I myself have been lucky enough to spend a few years at places which may eventually be regarded this way: the differences with the workaday places are preposterous.

Other factors Murray holds as important (as a good statistician always has a linear regression model) besides elite cities: wealth, AR(1/2) (aka important people were there before you), war and civil unrest ("War is the father of all") and a bullshit political factor he calls "freedom of action." I say it's bullshit because it is so mooshy as to explain absolutely nothing. I think it starts out OK in that the idea that some political systems might be better than others for innovation is a reasonable one, but honestly the system itself probably doesn't matter at all: the conditions of the individual and the social milieux are what probably matter. Can people speak and share thoughts or not? Late Venice and early Florence were both republics; you could say whatever you wanted in Florence (it was pretty much chaos in the streets) where making fart jokes could land you in The Leads in Venice.

There are a few other criticisms I might make; mostly for speculations that Murray failed to make. Murray appears to be about as much a straight laced boomer normie as is physiologically possible: he's obviously a man who wants to be taken seriously as a scientist -back in 2000 or whenever he was putting the thing together, it probably seemed fairly unlikely the orcs who ruined his reputation would ultimately "win," so leaving weird ideas out is quite understandable. These are speculations: I may eventually follow up on them in some analogous linear regression tier research. I think they deserve to be taken seriously, but unlike Murray I am not an academic and don't give a shit if I'm denounced for saying them. I'll already be denounced for suggesting you read any of Murray's books.

Sexual repression: one of the things you notice if you read biographies of great men is the superiority of bachelors over married men. Wags like Mencken or Francis Bacon will tell you it's due to not having a wife and children nagging and distracting you, and I'm sure that has helped during the eras where they were nags and distractions. But simple sexual repression seemed fairly ubiquitous. Reading Watson's autobiography, that man was a horn dog: his sexual frustrations must have fueled his research as it was half of what he wrote about. Same with Feynman: when he was still doing good work, he was away from the company of women. America and Britain during their highest achieving times or imperial expansion were .... Victorian. Michelangelo is widely believed to have been a homosexual, and there were no gay bars in Florence in those days. In my own life, when I've been too busy to have a GF, these are the times when I've accomplished my greatest deeds. I don't know how this would be measured, but if it were true it would be awfully important. Now a days virtually everyone is at least a filthy wanker, maybe that's why everything sucks. How many Sistine chapels ended up a pile of goo in some grody gay dude's hairy asshole in a leather bar? How many solutions to the unified field theory ended up crust in some nerd's sock? It's not the kind of thing we're supposed to talk or think about, but sexual dissipation is something that humans have known to be unhealthy for the individual for millennia, and as recently as Unwin's Sex and Culture, they assumed it was also unhealthy for society, and provided a great deal of evidence to back up the assertion.

Dilution: there are probably more "scientists" and "artists" alive now than all of human history before now. One of my hard-earned pieces of wisdom is that an awful lot of them are stupid and unimaginative almost beyond belief; even the ones who have considerable technical achievements. Having such inert lumps of wood around turns the artistic and scientific process into an imbecile clerisy embedded in a disgusting bureaucracy. People who do become famous these days are not generally particularly talented, but they do have talented marketing agencies on the payroll. Even worse is in current year, actual criticism seems to be something discouraged at all levels and in all accepted venues. One must go on youtube to find actual film criticism; the rest of society, it basically doesn't exist. Criticize a scientific paper and it could be the end of your career (unless you manage to call your opponent a racist in which case it's the end of his career). One of things about great times is the sheer number of raspberries passed at merely workman-like works: read Cellini's autobiography for some choice examples of this in Renaissance Florence. This existed in physics right up until the 90s at least on the experimental side, and was one of the things I liked about it. For any progress, cultural or scientific, we need more raspberries at loser efforts. Even in the times of Kapitza people had to form smaller more critical groups for excellence to appear.

Multiculturalism: de Gobineau noticed and attributed it mostly to race. Whether or not this is true (and there is an argument to be made that Yamnaya descendents are genius space aliens compared to all others), it is very obviously true that there is a degree of settled multiculturalism and lack of civilizational confidence which destroys creativity and progress. America did its best scientific work after the Ellis Island flood was turned off from 1920-1965. Sure we had a lot of help with WW2 and communism refugees; they're a lot more similar to original WASP America than, say, the Andalusian Muslims were with Castillan Spaniards (basically Germans), and they were assimilating to a dominant and confident culture. It is worthy of note (Murray mentions it) that Iberian cultural production was lower than, say, Italian or Belgian: they're basically the same people. It could have been multiculturalism. It could also have been they were too busy taking over the world to write as many novels or paint as many paintings as the Italians. There are numerous examples of this; you can read Glubb who more or less said this, or you can contemplate Periclean Greece (pretty uniformly Greek) versus Hellenistic Greece (unabashedly multicultural) or Republican Rome versus Imperial. I think it's at least worth considering: while bureaucracies might work quite well in multicultural empires, that's not true of cultural production: most small groups of very productive people are fairly homogeneous.

Education: not the kind you think. Are you aware that most people who achieved great things didn't go to college, and almost none of them went to grad school? Well, it is a fact. Of course they all learned something; very often through some sort of apprenticeship or tutoring. There are a lot of economic studies that higher education drive the economy; I'm pretty sure they are all false. The economy drives mass higher education: you can't afford it otherwise. Most of human achievement happened before high school existed; compulsory secondary education was considered utopian 100 years ago. If you really want your kid to excel, hire a tutor or send him to an apprenticeship or at least an Elite school that teaches the kind of things high schools did 120 years ago (ancient Greek and Latin). Mass High School, College and Grad School education has probably destroyed more genius than it's created. Einstein got his Ph.D. at 21; imagine wasting his time until he was 28 or whatever is normal these days. College has probably always been an ill influence on cultural production, but it is now obviously actively harmful. There are probably comparable IQ shredders in history: compulsory military service, or long studies for the priesthood. I think the main takeaway here is that education doesn't help, and it probably hurts. Murray mostly didn't mention education, I guess because across the arc of history there basically wasn't any, but probably also because this message is quite unpopular. He does mention it in terms of "density of people who could do great things" but doesn't notice that training thousands of midwits and "head girls" to be career noodle theorists is probably holding the clever ones back.

There are other interesting nits one might pick. The role of Protestantism is discussed by Murray, but I'd flesh something like that out with Riesman's Lonely Crowd insights into the psychological furniture of the non-NPCs of the world. These are minor quibbles; this is a book of towering importance and will provide guidance to the best mankind has to offer for my reading for the rest of my life. You don't have to read it cover to cover (I did), but you should own it for your own continued education and reading.