Conditional probability: an educational defect in Physics didactics

Conditional probability is something physicists have a hard time with. There are a number of reasons I know this is true. Primarily I know it is true from my own experience: I had a high-middling to excellent didactics experience in physics, and was basically never exposed to the idea. When I got out into the “real world” of, say, calculating probable ad impressions this concept became of towering importance. It took me a while to grasp it, and I still occasionally struggle with the idea, but it’s actually pretty simple.

What is the probability a man is over 6’ tall? Well, in the US, you look at the normal distribution and find it’s about 14%. If you know both his parents are 6’ tall, the number is higher. If both his parents are 5’ tall, the number is lower. That’s a practical example of conditional probability. Making it super concrete, imagine you have a deck of cards. Probability of drawing an ace is 4/52. Probability of drawing an ace if (conditionally) 10 cards have been drawn with no aces is 4/42. Probability of drawing an ace if you pulled 10 cards and two of them are aces (conditionally) is 2/42. You can do it with urns or dice or whatever; make yourself happy with your favorite example.

Statistical mechanics seems like this is where you should learn such things in physics, since we have no independent probability theory classes. I looked in Reif and Ma, the two books I learned statistical mechanics from. Reif doesn’t have the concept in the index, though it mentions Markoff and Fokker-Planck (he does mention conditional probability here). Ma only mentions it to argue that he doesn’t need it to teach statistical mechanics (later bringing it back in various places in a sort of ad-hoc way: I shouldn’t have slept in so much in that class). Ma even manages to avoid mentioning conditional probability in his treatment of Fokker-Planck, a considerable intellectual achievement for a set of equations for calculation of a conditional probability. As such, most physicists end up thinking of probabilities as funny sorts of ratios that must add up to one, which is right for a lot of cases in physics, but which is not correct in the general sense. Most of the classical statistical physics done with canonical ensembles (aka most of it) assume we can ignore conditional probability. Stuff like non-equilibrium thermodynamics is going to contain a lot of conditional probability, since it is dynamic and one-way in the same sense as the above card game. Our one example of a non-equilibrium thermodynamic relation which rises to the level of a law, the Onsager relations, certainly uses conditional probability, though Onsager himself never mentions it explicitly. The fact that he never uses the words, nor are they used in didactic explanations probably keeps physicists from having a good think about the implications of conditional probability in this and in other places. Out of sight, out of mind.

There are more pedestrian examples of physicists missing out on conditional probability; I’ll list a couple below:

Jung/Pauli synchronicity. When I was a young pot smoking man, I read with great interest a book on the correspondence between Jung and Wolfgang Pauli on the subject of synchronicity. If you’re unfamiliar with the topic, the following clip from Repo Man explains it well; lots of weird coincidences happen, and our brains ascribe meaning to them. Feels a lot like psychic powers or something. The reality is, the otherwise incredibly meticulous Pauli didn’t know enough about conditional probability, even to the level of understanding the trivial Birthday Paradox. It’s all conditional probability: it’s only surprising because our brains don’t intuitively grasp how conditional probability works. The brain observes many things in a short period of time; if some of them happen to overlap in a conditional way over a human consciousness tier period of time (minutes, hours, a day or two), the brain flags it as something significant, even when it’s entirely expected, like a group of 23 people being 50% likely to have a shared birthday. Pauli is a lot smarter than me; arguably smarter than any living current year physicist whose name isn’t Roger Penrose, yet he missed this obvious thing. Probably because his life was a mess and he was drinking too much, but also because he was probably never exposed to the idea in school or anyplace else.

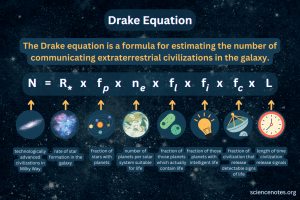

Fermi Paradox is a case where a Nobel prize winning physicist kind of left out important conditional probability aspects of a model. As we all know it is a calculation of there being other forms of intelligent life in the universe based on approximated probabilities. The Drake Equation lists number of stars in the universe, approximate probability of a planet in the habitable zone, age of solar systems, probability of life, intelligent life, civilizations, civilizations with space travel, etc. In the end he sums things up by multiplying all the numbers together, and comes to the conclusion that there must be intelligent life which we should be able to observe or which have visited us, or there are hidden and depressing dangers which wiped out all these space faring alien cultures. If you look carefully at what he did, you might never notice he didn’t use any conditional probability. Probably he elided over some important conditional probability. For example, most species go extinct in a way that fits the Survival model; there’s no reason to think intelligent ones have any special advantages, and lots of reasons to think any sort of megafauna, intelligent or otherwise is going to be at least as likely as any other species of megafauna to go extinct over time. This is just one of the conditional probability factors at work here. Though maybe earths are just rare, or intelligent life is unlikely in conditions where they might discover electricity (aka aquatic life). Conditional probability isn’t necessarily the right tool here for a quick look at orders of magnitude, but it is conspicuous for its continued absence in a calculation which heavily implies it might be useful.

The thermodynamic arrow of time. The arrow of time is considered a root problem in physics. Microscopic classical physics, there is no obvious arrow of time. The equations work the same way backwards as forwards. Yet you can assemble the microscopic equations into large ensembles and get the very irreversible laws of thermodynamics. Watanabe wrote an important paper on this subject in 1965 where he noticed that we leave out the conditional probabilities when formulating the statistical mechanical ensembles we use to calculate things and derive thermodynamic relations which make things like steam engines possible. Watanabe’s paper is influential with people with good taste, but mostly has been ignored. Certainly ignored in didactics, and often disputed for reasons which remain obscure to me. Rovelli and friends for example (linked above) think it’s a bad argument for various fiddley reasons which make no sense to me, but the idea of using conditional probability to ascertain where the arrow of time is coming from seems obvious. Of course I don’t know how to do it; I’m a mere statistical dabbler. Physicists resist this with all their might; you can find otherwise obviously intelligent people saying, effectively, “it just isn’t, OK.”

My favorite potential example of this is ET Jaynes idea that the mysteries of quantum entanglement go away when you think about conditional probability. I like this one a lot. Mostly because it dispenses with all the psychic powers quantum mysticism that has sprung up around the ideas of quantum mechanics. Also because it dispenses with quantum computers, which are both obviously fake and retarded. But mostly because Jaynes is the patron saint of physicists who make the jump to data science, and so, was uniquely qualified to bring this sort of thing up. Data science people have to know all about conditional probability: that’s pretty much what they’re doing, all day, every day. If nothing else, the fact that the main engagement with this idea in the literature ends up agreeing with it, rather than deboonking it kind of indicates that the conditional probability is weak among physicists. That’s not to say Jaynes was right, but the lack of informed argument against it indicates a weakness in the topic of conditional probability. If indeed the ideas of Jaynes turn out to be true (I’m in no position to adjudicate), this example will be held up by some future Thomas Kuhn type of thinker to be a spectacular example of a field of very smart people deluding themselves with didactic deficiencies, mathematical ignorance and group-think. As Mencken put it:

The liberation of the human mind has never been furthered by such learned (pedant) dunderheads; it has been furthered by gay fellows who heaved dead cats into sanctuaries and then went roistering down the highways of the world, proving to all men that doubt, after all, was safe - that the god in the sanctuary was finite in his power and hence a fraud. One horse-laugh is worth ten thousand syllogisms. It is not only more effective; it is also vastly more intelligent.

As an aside, I found another contemporary researcher who seems to take the conditional probability approach to get rid of quantum woo. I haven’t read his papers in detail, but they seem to be thoughts along the same lines as Kracklauer and others mentioned in the previous article. It’s entirely possible that entanglement is exactly what Scott Aaronson thinks it is, but the fact that its one application is only useful for pumping up fraudulent penny stocks thus far, I mean, I dunno considering the above it wouldn’t surprise me if the big wrinkly brains got this one wrong.

I suppose statisticians also have a hard time with conditional probability with Simpson’s “paradox” being a prime example, and Berkson’s paradox being a less known one. Contemporary statistical practitioners aren’t supposed to be deep thinkers though, so they get a pass.

Jaynes book is a must. It's online, if one wants to dabble before buying, since it's not cheap. Worth it, though.

David Stove is another author your readers will like. Basically proves the underpinnings of Jayne's mind projection fallacy. And of course proves all probability is conditional. And a matter of the mind.

We get a lot of physics and engineering failures in my line of work (mostly Chinese, but then who isn't Chinese these days?). Often surprised how hard it is to walk them through ML-ified versions of basic econometric models. Especially time series stuff, stationarity &c. Come to think of it, also conditional probabilities. Surprising as I usually think of physics failures as smarter than economics failures but perhaps it comes down to training.